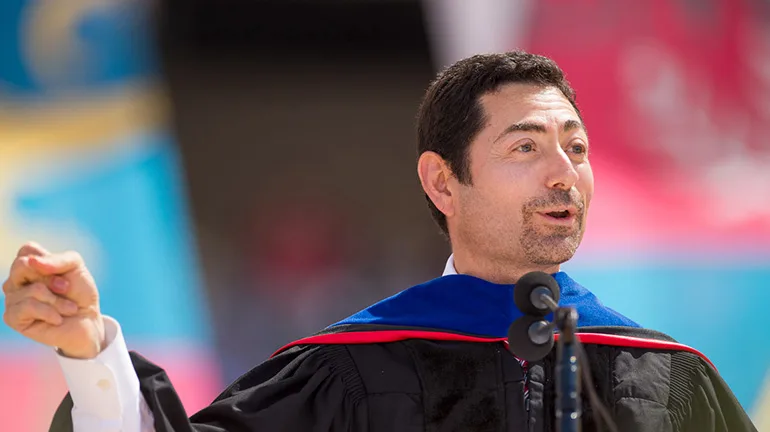

Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar, President of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and former Associate justice of the California Supreme Court, gave the keynote address at Stanford University’s 126th Commencement on June 18, 2017.

The following is the prepared text.

Thank you for that incredibly generous introduction. President Tessier-Lavigne; Provost Drell; generous trustees; dynamic faculty colleagues; patient deans; staff who don’t get enough credit but keep Stanford running; relieved and proud parents who made today possible – and 0-17! Today the sun shines on you. Rightly so. Just a decade and seven years ago, I was sitting where you are. So I’m deeply humbled to share this moment with you. I’m moved to my core by affection for Stanford, and blessed by having taught and learned from some of you graduating.

Here’s the last time I felt this humbled at Stanford: My son was in preschool at Bing Nursery School on the edge of campus. I went to observe him. I spoke in Spanish to him as I often did – hoping a little would stick. Then he realized his friends were puzzled because I was speaking another language. He turned to the rest of the 4-year-olds and said: “That’s my papi. He wants me to learn Spanish, but also, he only knows a little bit of English.”

He should have stopped at “he only knows a little bit,” because that’s how I feel today. Knowing I would feel this way, I sought reassurance from my optimistic daughter. Yet this diehard Hamilton musical fan gently explained that nothing I did today could be as good as Penn’s commencement address in 2016 by her hero, Hamilton creator Lin-Manuel Miranda. Maybe we should just watch that.

But look, even judges can find morsels of inspiration. So I thought of sharing a draft of my own hip-hop musical – about an unpredictable, privileged New Yorker who makes it to the Oval Office and faces one crisis after another. Would you like to hear a few lines? The main character is, of course … Franklin Roosevelt, the subject of a book I wrote. Here goes:

Check out this LONELY–ONLY child of UP–state New York, in his mouth a silver FORK, with so little need to WORK. How does he BECOME the famous FDR, steward in a global WAR, and protector of the POOR? In their FACES you see the EMBRACES of this man in leg-BRACES!

The SILVER–TONGUED future father who lost his FATHER got a lot farther by acting a touch NICER, by being a bit WISER, by picking his wife SMARTER, by thirty–EIGHT, he tries out for V.P. ‘cause he won’t WAIT for FATE!

Now you’ve had a chance to hear firsthand why I should stick to my knitting. Which I’ll do. But to be clear, that bit about picking a spouse smarter than you – it worked for me. As for FDR, he was nothing if not a deal-maker. In his honor I’ll make you this deal: Keep the little supercomputer in your pocket at bay a few more minutes; I’ll use just 12 more. I’m going to share three reflections. I’ll ask you to remember one thing – about choosing what makes it to the core of our awareness, and what’s left at the edge – then you’ll be on your way.

My first reflection is about context: your good fortune and mine. Think of the world as it stood when FDR was a baby. Back then, nearly 40 percent of children around the world died before age 5. Today only 4 percent of children do. As my grandfather was teaching himself to read in rural Mexico a century ago, global literacy was 12 percent. Now it’s 85 percent of the world’s population that can read. In her northern Mexican kitchen, my grandmother worked miracles with corn, cilantro, tomato, serrano peppers – and sadly, lard. Her own grandparents could have scarcely imagined the bounty of nutrition at her fingertips.

That so much food is grown by so few people is a miracle, making it possible for us to study artificial intelligence and art history. We make so much water clean enough to drink that we can literally shower in it. As we celebrate your graduation, we have the means to enjoy lives that are not only more fulfilling, but twice as long on average as when my grandfather was born. You are the heirs to this gift of progress, across time and for some of us across borders. It is a testament to creativity; to science; and to our ability to understand and affect how society changes over the merest instant of historical time.

My father’s father began life as a shepherd in rural northern Mexico and had no formal education. Leaving his parents at 12 he struggled to make it to the border city where I’d eventually come into the world. Later he worked to create a municipal waterworks bringing the city clean water. He faced not only engineering problems but the complacency and corruption that to this day can frustrate even the most laudable efforts to improve public health. Yet he succeeded in the end – and clean water helped strengthen the city’s health literally and figuratively.

The water in the river dividing Mexico and the United States where I was born also told a story: how people experience different lives and levels of well-being across borders, even as trade and migration made our world smaller. As a kid, I used to look across the river dividing Mexico and the United States. On the other side I saw a place that looked cleaner and richer. It was. Per capita GDP in America then was four times what it was in Mexico; like Egypt today sharing a border with the United Kingdom. As trucks rumbled north piled high with okra, I pondered how fate sorted the babies to one side of that border or the other.

Years later my family followed those trucks to this country in search of a better life. Then as now, I was drawn to this complicated and beautiful country’s commitments – however imperfectly realized: to finding a place for immigrants, like my brother and me, or my mother-in-law, who escaped from North Korea as a child. To public schools like the one that prepared many of you – and me – for college. And to the higher ideals JFK evoked in his inaugural address when he spoke of a place where the “strong are just,” the “weak secure” and the “peace preserved.”

These ideals are not easily realized. Nor can we erase the concerns of people whose lives are at the edge of subsistence. As Angus Deaton reminds us, a billion people still have the short life spans and bleak living standards their forebears endured. I would add examples from our own body politic at the edge of our awareness. Somewhere in America this morning, a man who still hungers for work decides to give his plasma – for money to support his family. To leave occluded his life also risks neglect of another life – that of his little girl, who’s never heard someone tell her that she could grow up to attend Stanford. There’s no point and some peril in facing the challenges our world has in store so divided, or deprived of wisdom and talent waiting to be tapped. May knowledge bring light to these divisions and perils.

Which brings me to a second reflection – about what it takes to expand knowledge and bridge divides. Some of my most moving moments of learning happened right here. Yours, too. Falling in and out of love. Discovering the subtle melody, as I once did, connecting psychology and economics. It’s learning to speak up and forge coalitions. How to dialogue over what’s true and what’s not, instead of just fighting over what you believe. It’s the people at the edge of your awareness becoming close friends, even though you join a Black Lives Matter protest and she’s the daughter of a cop and thinks you have policing all wrong. You’ve conveyed high expectations of this place as it’s conveyed its own, and you’ve seen it work its quiet miracles.

The last decade and seven years have also made clearer something else. Our core knowledge and values are forged to a considerable extent by the days that don’t end at all as we expected, and instead expose us to people and ideas at the very edges of our daily lives. Maybe you’ve experienced something like a bus ride I took when I was a graduate student. I’d been volunteering in San Jose and one evening missed the last Caltrain. The ride on the 22 bus late that night was not short. Two riders were kvetching about the pains of reentering society after being in prison. Their words would echo in my mind years later when I worked at the White House. After an hour, a fight nearly broke out between two other passengers. Both were drunk. The driver calmly parked the bus and announced on the PA that we’d stay parked until the two gentlemen keen to fight got off the bus or calmed down. As the passengers groaned, the belligerents eyed each other like Burr and Hamilton. “I’m not throwing away my … bus ride!” said one, as I recall. The other retreated, scowling. The bus rumbled on, and I pondered how much else the driver could add to what I was learning in graduate school and law school about resolving disputes.

What these moments often evoke is the difficulty of bridging divides: between people who disagree or even want to fight, between ideas difficult to reconcile, or simply between ourselves and those we encounter, as some I have encountered over the years, with starkly different lives – like the undocumented man with an American family sitting behind me in a Greyhound bus I once rode, telling his life’s story to the man next to him not realizing this man is an immigration agent who’ll detain him a few hours later in Brawley, California. The child of farmworkers from the border who grows up to work in the border patrol and feels pride in her work. The man who no doubt loves this country just as much as I do but doesn’t get why I’m so determined to make sure language is never a barrier to a domestic violence survivor who needs protection in our courts.

The opportunity to see these divides – and bridge them – now passes to you, 0-17. Take from your experience here what you need. Keep at it and listen, because we rarely persuade people we don’t understand. And keep playing your part in our shared effort to separate fact from fiction. Remember how much this endeavor pivots on guardians of integrity like universities that depend on people who – as Learned Hand put it – do not carry a sword under a scholar’s gown.

My third reflection is about the value and varieties of public service. Architects sometimes say the best architecture makes us forget how hard it works. So it is with the architecture of our civic life. In a democracy, no leader’s as important as the civic architecture he or she swears to protect and support. Aside from being a husband, a father and an American, being in public service has been the greatest privilege I’ve had. For any of us such opportunities can take many forms: strengthening one of these guardians of integrity in education or the judiciary. Helping translate a scientist’s findings into plans for keeping safe our food and water. Growing a nonprofit that will enable that whip-smart little girl living in poverty to develop and apply talents that might not otherwise be discovered. The reward isn’t fame or personal gain. But it’s a singular privilege to see how our civic architecture works, where it doesn’t, and how we protect and adapt it – using what we learn, our own hands and an eye to nuance.

You might do that by engaging with democracy, volunteering for a campaign that inspires you. You might have to brace yourself and observe, as I did a decade ago, the mix of hope and hostility from residents in a foreclosure-laden neighborhood. Or maybe you’ll observe how votes are tallied at a caucus election. I was at one in Nevada, at a gym. At the very edge of my awareness, distracted by a smartphone, I saw how the caucus chair made a rounding error – one I almost missed. Because I corrected the chair’s mistake – a mistake that worked in our favor – the campaign I supported lost a delegate. What we gained protecting the process was worth far more.

Seek out these opportunities to share your good fortune. Listen for clues about how to reconcile our aspirations and our always-messier realities. The choices we make in our civic lives don’t always come pre-wrapped in bundles marked “important,” addressed to a judge or the FBI director. They come to the civil servant asked by her boss to ignore the rules, or the voter whose frustration begins degenerating into rancid cynicism. Time and again in public service, you’re handed reminders of how institutions depend on our acts or omissions, our ability to see the details playing out at the edges, shaping the architecture that in turn leaves an imprint on us as we age.

My grandfather died when I was 8. His dark brown eyes would be wide with wonder if he could take in our age of miracles. He’d soon guess what you know: that more change is coming – and with it, hard choices. About how we deliver justice to everyone in any language; how we reconcile freedoms of those who can prosper in any country with needs of those stuck and struggling in their own country; how we build convolutional neural networks not only for getting us to buy something but helping us stay resolute not to; how we face loss of dignity from lost work; how we confront climate change; how our technology can feed the world without feeding machines too much power over our lives.

Today I’ve sought to remind you of your own power – by talking of the “edge” and the “core.” Yours and only yours is the power to embrace what’s at the edge of your awareness: the families getting left at the periphery in the larger story of human progress. What we learn outside formal channels of education. The emotions subtly driving us to anger. The unsettled feeling that we’re not quite ready, if indeed we ever will be, to lethally arm that sleek, fully automated drone. The profound ways our institutions depend on our acts and omissions. The molecule or data point stubbornly refusing to behave as predicted. Always it’s within your power to move those concerns closer in, to your heartland of awareness.

Take what’s at the edge of your awareness seriously, and it becomes your own edge – your advantage. Your power to see the dangers others face, and in their fate, yours. Your ability to see the little miracles playing out in a Fresno poetry slam and not just a Silicon Valley coding camp. Your means to engage the world and each other as I’ve seen you do.

Now it’s your turn, 0-17 – heirs of the gift of more life, health and wealth. And I share this last request. Keep close to you a letter – one you can write tonight and address to your future self. One you can read in 10 months or 10 years as it sinks in just how finite your time on this planet really is. Use the letter to list the values at your core. What you did here that fed your soul and quenched its thirst for understanding. What’s been at the edge of your awareness that you’ll place in that letter so it’s nearer to your core. How you might bridge your own dreams and those of a family in the periphery with its own heartbreakingly simple goal: “Stay nourished. Stay safe.”

It was no accident that FDR spoke of freedom from fear or hunger. Whatever his limitations, the former LONELY-ONLY child sought a world where people could dream because they could feel safe and nourished enough to do so. That today you’re living that dream is at the very core of our celebration. Tomorrow, I’m betting on you, 0-17: to share that gift, to keep sharp your peripheral vision and to celebrate these ideals, in any language, as your days turn into decades. Thank you, and God bless you, 0-17!